WWRWED?

The Emersonian question about AI

For at least half a century, if not since basically forever, it has been unfashionable to take R. Waldo Emerson too seriously as a philosopher. He does, however, have a theory of the world, and I’ve found it useful.

Emerson’s idea, to put it in my own untranscendent prose, is that the world consists of circles. You are one; I am another; the world is yet another. Some of these circles are nested; others intersect. The meaning or truth of each is a bit of a secret, because truth is in the center, and we only see surfaces. That doesn’t mean surfaces are without value. They are, in fact, the only possible access to the truth in another person. Truth radiates, or grows, from the center of each circle to its circumference; the surface is the only place it becomes legible. Along that radiative journey, however, truth is liable to get waylaid, to be interfered with. Unfortunately, one of the most pernicious kinds of interference comes from the truth radiating out from other people’s circles, which are always distracting and sometimes even compromising. Somewhat paradoxically, however, Emerson believes at the same time that the truth at the heart of every circle is the same, in essence. This leads to somewhat conflicting imperatives. Out of respect for truth, you must listen to everyone you meet as if they were as valid a source of truth as you—because they are—but you must only follow the guidance of the voice that emanates from inside you. Truth is incarnated in every individual, and unfolds in every individual in a distinctive way that will be her unique contribution to the world if, and only if, she can hold on to it—stay faithful to it—resist the temptation to soften or temper it in deference to the truth emanating from the other people she meets as she goes through life.

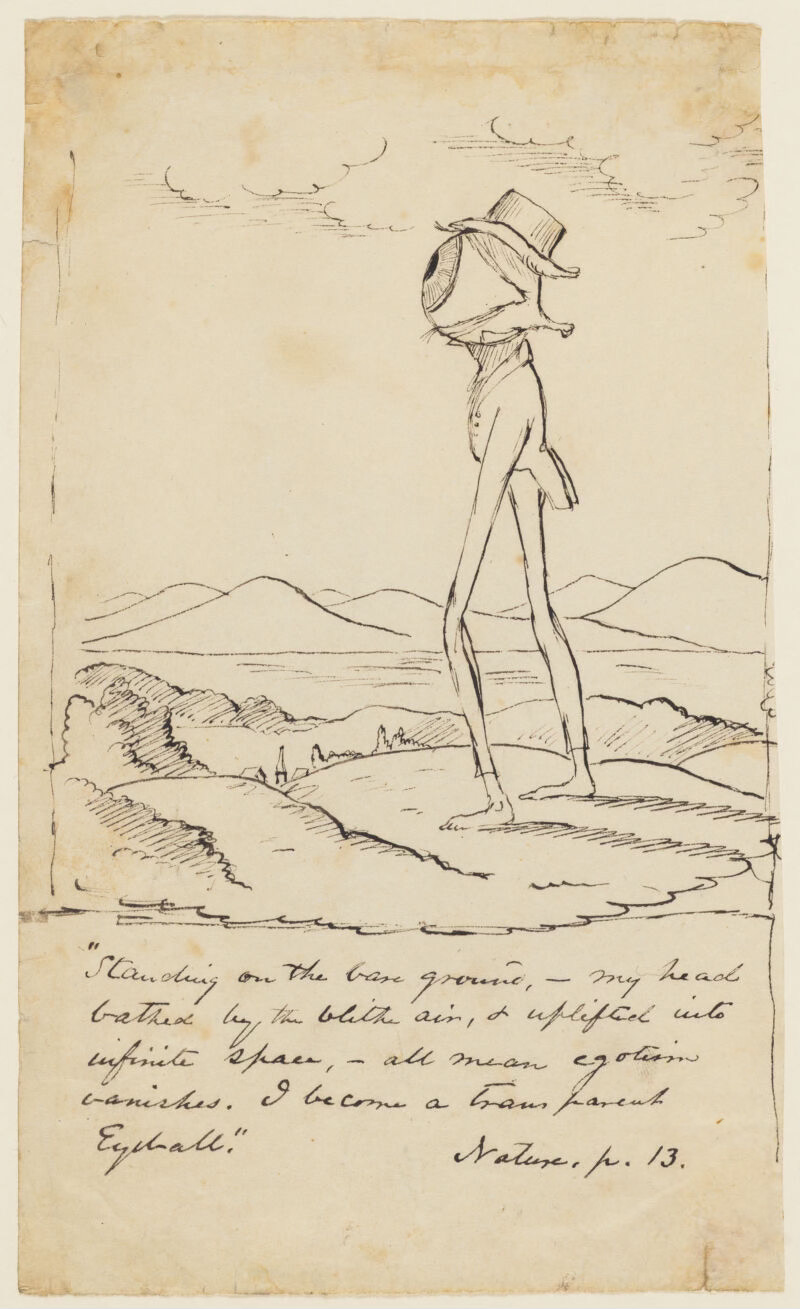

Thus the primacy of the eyeball in Emerson’s cosmology: an eyeball is a circle that lets the light of the world in, that focuses it. To reach the truth (“meaning” is as good a word as “truth” for what is being sought), you have a choice of two paths: listen to the still, small voice that speaks in your soul, or let in the light of the world in a capacious, almost self-annihilating spirit. Emerson believes that the two paths lead to the same place, that the whole, in the end, reveals the same truth as the center.

It’s better, in this worldview, to avoid becoming another person’s acolyte, because of the risk that by doing so, you’ll slight your own genius. But if you do happen to become an acolyte, don’t worry. It needn’t be a dead end, because if you follow another person in a spirit that is generous enough, you will eventually exhaust them, pass through them—and come back to yourself.

The only thing you absolutely mustn’t do, in Emerson’s philosophy—the one thing that blocks you from reaching the truth and meaning of your single, special life—is let your judgment be supplanted by a consensus or an average. You must never accept the received opinion instead of coming up with one of your own, because once you give up seeing for yourself, you are lost. The average is the dense gray medium that the light of truth is supposed to struggle to penetrate. It is the sum of all the compromises the light tries to get through. The dross of this world. If you’re willing to let what’s popular with others take the place of the truth, you might as well not have lived.

I have found this philosophy useful, and, I’m afraid, true. Have I always lived up to it? No! I try never to look at Goodreads, but I do look at Rotten Tomatoes, and I usually cook from recipes instead of inventing each dish from first principles. Still, I believe Emerson was right. And I believe that if he were alive today, he would condemn artificial intelligence.

If you believe every human being has a soul, in an Emersonian sense—that is, a unique portal inside their heart through which they can hear the voice of God, if they listen in the right way—the danger AI poses is clear. AI is the average. It is the digestion and recapitulation of what has already been said. As such, it is exactly what the scholar (Emerson’s term for a seeker of truth) must avoid: pure opacity. In the limit case, this is obvious: if everyone in the world gave up writing in their own voice, and all future prose were devised instead by artificial intelligence, no new truth would ever come into the world. But I think it’s true incrementally, as well. The more often people ask AI to write their emails, the less human soul is expressed into the world. Some intellectuals are prone to romanticize gambling, and to condescend to denunciations of it as schoolmarmish, but the Emersonian reason to abstain from gambling is the same, more or less, as the Emersonian reason to abstain from AI: when you gamble, you hand over to chance a portion of the head-to-head combat that your will would otherwise have to make with the world. You give up an opportunity for intentionality. You voluntarily increase the amount of your life that is subject to materiality, to the chaos you’re supposed to be trying to see through.

This is an awfully high-minded reason not to use AI, I am aware. But I am afraid I’m a little worried about it.

Thanks for posting this, Caleb. I shared it with my class on the Transcendentalists, which is just wrapping up in Vermont ... I am mildly obsessed with that Christopher Pearse Cranch cartoon & project it whenever there is an excuse. Have a happy thanksgiving. Yrs, B.