On 1 July 2024, the Supreme Court awarded former and current Presidents sweeping immunity from criminal prosecution—protecting them from criminal liability for almost any act performed while in office, so long as the act was performed in the President's capacity as President.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts ruled that a President is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for any exercise of his “core constitutional powers,” such as issuing pardons, nominating ambassadors, and firing heads of department [Roberts 9], and must be presumed immune from criminal prosecution for any other official act, unless it can be shown that prosecution won’t in any way conflict with the “authority and functions of the Executive Branch” [Roberts 14]. The Roberts court also ruled that a President may not be subjected in court to any examination of his motives [Roberts 18], which implies, according to Roberts, that even in a trial of a President for his unofficial acts, a prosecutor may not introduce any of a President’s official acts as evidence [Roberts 30].

The three liberal justices on the court wrote strong dissents, which so irritated Roberts that, toward the end of his opinion, he accused them of adopting “a tone of chilling doom” and relying on “cherry-picked sources” [Roberts 37–38]. Why so emotional? he seemed to be asking. He himself had raised his eyes toward legal eternity (“we cannot afford to fixate exclusively, or even primarily, on present exigencies,” he wrote [41]), and if he had made the effort of rising to the dispassionate, slightly inhumane plane where eternity may be duly thought through, why couldn’t they? It’s a mistake to pay too much attention to the messy, distracting corporeality of Donald J. Trump, was his implication. Instead of the mere case at hand, focus on its abstract and perpetual ramifications.

There is something to the empyrean angle, of course. Supreme Court decisions often get turned inside-out like gloves by the justices of later generations, so there’s virtue in thinking beyond the case at hand. Speaking just for myself, a part of me is always ready to worry that I’m listening to my heart when I should be listening to my head. So let’s consider; let’s be cool. Is Roberts’s reasoning sound? Has Sotomayor, who wrote the stronger of the two dissents, misread the historical evidence of the intent of the Constitution’s Framers, or failed to take into account the implications of intervening rulings and case law?

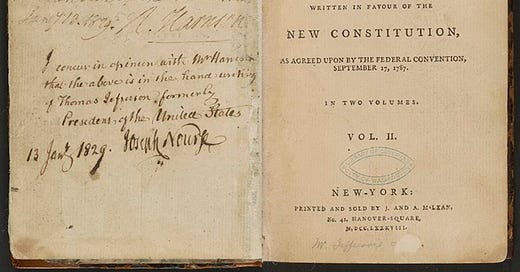

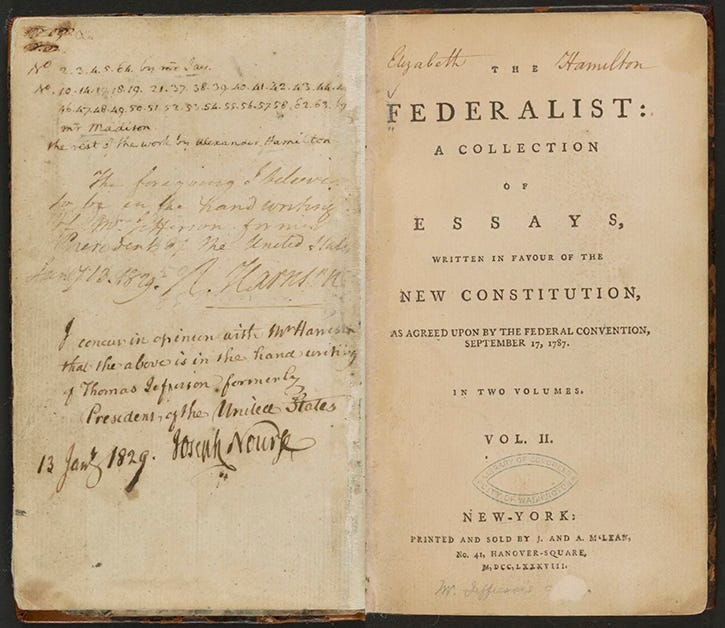

One of the things that seems to have most annoyed Roberts is that Sotomayor quoted scripture at him, scripture in this case being The Federalist Papers, the preeminent source, especially among originalists and other legal conservatives, for documenting the Framers’ own rationale for the Constitution. Sotomayor noted that in Federalist No. 69, Alexander Hamilton wrote that Presidents, in addition to being subject to impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors,” are “liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law” [Sotomayor 6, quoting Federalist 69]. What a lovely phrase that is, by the way: “the ordinary course of law.” There’s another off-handed reference by Hamilton to the President’s vulnerability to plain-old criminal prosecution in Federalist No. 65, where it is again seen as a punishment supplementary to impeachment: “After having been sentenced to a perpetual ostracism from the esteem and confidence, and honors and emoluments of his country; he [the President] will still be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” And Hamilton refers to the liability yet again in Federalist No. 77, where he suggests that the Constitution makes the Presidency safe “in the republican sense” (i.e., arranges the Presidency so that it will not easily turn into dictatorship) by subjecting Presidents to election every four years, by making them vulnerable to impeachment by Congress, and by keeping them vulnerable to “the forfeiture of life and estate by subsequent prosecution in the common course of law.” Life! In the good old days, take note, a politician as unradical as Hamilton seems to have believed that a President who committed treason might have to pay with his head.

Roberts complains that in the quotes that Sotomayor takes from Hamilton, Hamilton doesn’t specify whether the President could be prosecuted “for his official conduct” as opposed to his private conduct [Roberts 39]. Roberts’s implication is that the verses of scripture aren’t therefore all that pertinent. But as Sotomayor points out, Hamilton doesn’t specify because Hamilton doesn’t seem to have seen the need to make any such distinction. He seems to have believed Presidents were responsible for all their crimes.

As did other Framers of the Constitution. Sotomayor quotes a speech that Charles Pinckney, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, gave in the U.S. Senate on 5 March 1800. Pinckney recalled that

No privilege of this kind was intended for your Executive, . . . . The Convention which formed the Constitution well knew that this was an important point, and no subject had been more abused than privilege. They therefore determined to set the example, in merely limiting privilege to what was necessary, and no more. [Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 3: 385, quoted in abridged form by Sotomayor at 7]

Roberts considers Pinckney’s testimony to be “the principal dissent’s most compelling piece of evidence” [Roberts 39], and he rebuts it in two ways. First, by writing that Pinckney is merely stating an argument that has long since been discredited, namely, “that any immunity not expressly mentioned in the Constitution must not exist” [Roberts 39].

In this sentence of Roberts's, the word “any” is doing a lot of work. In Nixon v. Fitzgerald, decided in 1982, the Supreme Court did rule that Presidents are immune from civil suits for damages even though no such immunity is spelled out in the Constitution. The 1982 court reasoned that the separation of powers implied by the Constitution was meaningless unless the President’s time and attention were protected from interference; the court judged that having a “vigorous” (Hamilton’s word) executive branch was more important than redressing the injuries that a President’s actions might happen to cause to individual private citizens. So yes, there now exists a Presidential immunity from civil lawsuits, not expressly mentioned in the Constitution. Moreover, courts have long been chary of forcing the executive branch to make public its internal deliberations, even when such disclosures might be of use in a trial, because courts have judged it important for the President to have access to candid advice, which might not be forthcoming if advisers worried that their words could appear as trial exhibits some day.

There is no evidence, however, that the particular immunity at stake here—a Presidential immunity to criminal prosecution—existed before 1 July 2024, certainly not in any explicit form. Perhaps sensing that he hasn’t altogether put paid to Pinckney, Roberts moves on to a second line of attack against Pinckney—a rather strange one. “Pinckney,” Roberts writes, “is not exactly a reliable authority on the separation of powers: He went on to state on the same day that ‘it was wrong to give the nomination of Judges to the President’—an opinion expressly rejected by the Framers” [Roberts 39].

The first thing to say about this attack is that Roberts seems to be engaging in a forensic method no more searching than the one I’m deploying in this blog post—namely, looking up Sotomayor's footnotes. He doesn’t seem to have at his disposal any historical resources he has discovered for himself. The second thing to say is that even just on the face of it, Roberts’s comment doesn’t seem likely to be true. When I first read it—before I had even read Sotomayor's dissent, let alone looked up the relevant page in the Records of the Federal Convention of 1787—I scribbled in the margin, “But why would Pinckney's having an opinion not later considered canonical make him an unreliable reporter of the consensus at the Convention?” And indeed, if you go look at the source that records Pinckney’s comments, you’ll see that in his remarks in the Senate in 1800, Pinckney is clearly distinguishing (a) his longstanding personal opinion that it was wrong to have the President nominate judges, from (b) his recollection that it was the sense of the Convention that the executive branch should not be shielded by any privilege. How could Roberts have looked at the page in question without seeing this? Is he that sloppy a reader? Or that tendentious a one? One begins to suspect he may not be operating on a plane quite as empyrean as he would like his readers to believe.

Furthermore, Hamilton’s and Pinckney’s belief seems to have been widely shared in early America, as Sotomayor documents by quoting a speech that James Iredell, later one of the Supreme Court’s first justices, gave on 28 July 1788, when North Carolina was debating whether to ratify the Constitution: “If he [the President] commits any crime, he is punishable by the laws of his country, and in capital cases may be deprived of his life” [Debates on the Constitution 4:109, quoted in abridged form by Sotomayor at 7 n 2]. Life again! One gets the impression that the possibility of hanging the President was rather dear to the hearts of the first generation of Americans.

Even more telling, the same belief is also present in the text of the Constitution itself, Sotomayor argues. The Impeachment Judgment Clause limits Congress’s potential punishment of the President to removal from office and the stripping away of honors and pay, but then adds that “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law"“[U.S. Constitution 1.3.7]. Sotomayor puts the word “nevertheless” in italics, to emphasize that the Framers did not intend for impeachment to preclude or preempt criminal prosecution, and points out that bribery, one of the “high crimes” explicitly named as a matter for impeachment elsewhere in the Constitution, involves a President’s official acts almost by definition. If anything, Sotomayor may be underselling her case here. It’s also hard to imagine how a President could commit treason—the other “high crime” called out by the Constitution for impeachment—without deploying his official powers as President. How could a President commit treason if not by taking advantage of his command of the military, or by mounting the bully pulpit and calling for insurrection or civil war? It’s unimaginable that the Framers of the Constitution would have wanted to immunize from criminal prosecution a traitor who turned the armed forces, or a segment of the public, against the Constitution he had sworn to uphold. Indeed, what else could the Framers have been thinking of when they referenced the potential hanging of Presidents so often and so cherishingly? When the Impeachment Judgment Clause is read in the context of the quotes from Hamilton, Pinckney, and Iredell, all of which follow the same semantic pattern—stating that the Constitution provides for impeachment of the President by Congress, and then clarifying that this punishment is in addition to criminal prosecution in the ordinary course of law—it becomes irrefutable that the Constitution states that Presidents are not immune from criminal prosecution. A Presidential immunity from criminal prosecution is literally, explicitly unconstitutional.

Roberts makes the same retort to the Constitution that he makes to Hamilton, namely, that the Impeachment Judgment Clause “does not indicate whether a former President may, consistent with the separation of powers, be prosecuted for his official conduct in particular” [Roberts 38]. This is weak, since Roberts doesn’t provide any evidence that Hamilton, or any other Framer, thought any such distinction should or could be made. But I’m not an originalist, nor, for that matter, is Roberts, though most of his conservative allies on the Supreme Court are. Let’s go ahead and admit that a criminal immunity for the President's official acts is being established by decision in Trump v. United States—is being made up. Or, to speak more politely, is being inferred. And let's take a look at this new construction.

Once you admit it’s new—once you strip away the gilding of historical inevitability and admit that the Roberts majority is working a change in America's political economy—the change becomes easier to see. Sotomayor for her part insists on the novelty of the Roberts majority's creation. “Every sitting President has so far believed himself under the threat of criminal liability,” she writes; the threat “has been shaping Presidential decision-making since the earliest days of the Republic” [Sotomayor 17]. If Ford hadn’t pardoned Nixon, she writes, Nixon would likely have been found guilty of deploying the FBI to obstruct justice in the Watergate case—an official act and therefore immune, under the new Roberts dispensation. Indeed, Ford’s pardon of Nixon was only meaningful because Nixon was understood to be liable to criminal prosecution [Sotomayor 9]. Reagan was investigated for the Iran/Contra program because if he had been found to have been aware of and to have directed it, he would have been prosecuted for it even though that illegal operation, too, would as of this week be considered an immune exercise of the President’s official powers [Sotomayor 10].

Sotomayor is biting about the clumsiness of the new construction. In the case before the court, she points out, Trump isn’t charged with any crime that involves what Roberts labels a “core” power of the Presidency, so there was no need, juridically speaking, for Roberts to isolate the President’s “core” powers and bestow on them absolute immunity [Sotomayor 23]. Moreover, since Roberts is willing to include in his “core” exemption any discussion between the President and the Department of Justice, the boundaries around the created category are so extensive as to be almost indistinguishable from the official acts to which Roberts claims to be granting only presumptive immunity [Sotomayor 24]. That presumptive immunity, by the way, Sotomayor considers to be a hollow game. The conditions that Roberts sets for overcoming presumptive immunity, after all, are a near impossibility, just by inspection. How could a risk of criminal prosecution fail to hem in the power of the executive branch? “It is hard to imagine a criminal prosecution for a President’s official acts,” Sotomayor writes, “that would pose no dangers of intrusion on Presidential authority in the [Roberts] majority's eyes” [Sotomayor 11]. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, similarly, calls Roberts's claimed distinction between absolute and presumptive immunity “illusory” [Jackson 14].

Roberts's whole edifice, Sotomayor shows, turns out to be sucked not from between the lines of the Constitution but from between those of the Supreme Court’s 1982 Nixon v. Fitzgerald ruling, which she calls the “one arrow in its [the Roberts majority’s] quiver” [Sotomayor 12]. An arrow shot far beyond its target, she argues. To insulate the President from civil lawsuits is to grant him a significant privilege, but to immunize him from criminal liability is to place him almost entirely above the law (even Roberts, it should be said, preserves a President’s liability for private crimes like theft or sexual assault). In Nixon v. Fitzgerald, the court weighed the vigor of the executive branch against the value of remedying private civil torts, and chose executive vigor, but even in that decision, the justices wrote that “there is a lesser public interest in actions for civil damages than, for example, in criminal prosecutions” [Sotomayor 14]. Indeed, the more powerful a public official is, the greater the public’s interest in keeping him accountable. “When Presidents use the powers of their office or personal gain or as part of a criminal scheme,” Sotomayor writes, “every person in the country has an interest in that criminal prosecution” [20]. The amount of interference to be fended off, meanwhile, is radically different. Anyone can file a civil lawsuit, however frivolous, but justice departments are constrained in issuing criminal charges by department policy and by grand juries [15]. It’s a little weird, moreover, that Roberts considers it “a great burden” for the President to have to obey laws; the Constitution already requires him to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,” so presumably he’s already paying a fair amount of attention to them [18].

And it’s absurd to treat executive vigor as if it were the only governmental virtue. Jackson, in her dissent, quotes a 1926 dissent by Louis Brandeis, explaining that the separation of powers—the crux of America's political economy—was adopted by the Framers in spite of its obvious inefficiency. “The purpose was, not to avoid friction,” Brandeis writes, “but . . . to save the people from autocracy” [Jackson 19]. If the Roberts majority genuinely valued governmental efficiency more highly than civil damages, there would have been no reason for them to have ruled last week, in Loper Bright, that experts in federal regulatory agencies are no longer entitled to deference in the courts when challenged by private business interests.

The list of flaws in Roberts's reasoning goes on. Even one of the justices who concurs with him, Amy Coney Barrett, finds his willingness to exclude a President’s official acts from evidence unwarranted [Barrett5–6]—an exclusion that Sotomayor, for her part, calls “nonsensical” [Sotomayor 26n5]. Sotomayor further points out that the risk that jurors in the criminal trial of a President might be politically biased isn’t “unique” to a case like Trump v. United States, as Roberts claims, but is inextricable from any effort to hold a politician accountable in the American justice system [Sotomayor 27].

The Roberts majority doesn’t seem to want the American justice system to try. Its ruling in Trump v. United States is remarkable for the paucity of the historical evidence behind it, its slipshod construction, and its failure to balance the concerns of democracy and justice against those of executive efficiency. It is opposed in spirit to the distinction Hamilton tries to make, in Federalist No. 69, between President and king:

The President of the United States would be an officer elected by the people for four years. The King of Great-Britain is a perpetual and hereditary prince. The one would be amenable to personal punishment and disgrace: The person of the other is sacred and inviolable. . . . What answer shall we give to those who would persuade us that things so unlike resemble each other? [Federalist 69, quoted in abridged form by Sotomayor at 6–7]

In the country Hamilton helped found and frame, his question can no longer be answered.